[2]:

import omusic

import omusic.chord as chord

import omusic.modes as modes

from omusic.scale import scale

from omusic import note_i2s

from omusic import note_s2i

from omusic import interval_s2i

from omusic import interval_i2s

from omusic import name_interval

from omusic import invert

from omusic import reach

from omusic import same_class

[3]:

print(scale("C", modes.MAJOR))

print(scale("C", modes.MINOR_BLUES))

print(scale("C", modes.MAJOR_BLUES))

['C0', 'D0', 'E0', 'F0', 'G0', 'A0', 'B0']

['C0', 'D#0', 'F0', 'F#0', 'G0', 'A#0']

['C0', 'D0', 'D#0', 'E0', 'G0', 'A0']

Music Theory

Music Space

There are two pre-defined “music spaces”:

NOTES_MIDIrepresents scientific names whereNOTES_MIDI[0]is \(\mathrm{C}_{0}\) andNOTES_MIDI[127]is \(\mathrm{C}_{10}\). Also,NOTES_MIDI[i]is the \(i^\mathrm{th}\) MIDI sound. This is the default option.NOTES_INTEGERrepresents pitch classes, whereNOTES_INTEGER[0]is \(\mathrm{C}\) andNOTES_INTEGER[11]is \(\mathrm{B}\). Also,NOTES_MIDI[i]is the integer notation for that class.

To use a music space, assign the corresponding variable to omusic.NOTES.

[4]:

assert omusic.NOTES == omusic.NOTES_MIDI

For readability, notes are often represented as strings.

The functions To convert

as a string (“C”) or (b) as an integer (“0”).

The following cells define two functions note_s2i and note_i2s that convert between these representations.

[5]:

for i in range(len(omusic.NOTES)):

assert note_i2s(i) == omusic.NOTES[i]

Check that key_s2i and key_i2s are each others’ inverse:

[6]:

for i in range(len(omusic.NOTES)):

assert note_i2s(i) == omusic.NOTES[i]

If the name of a note does not end with an octave (0 to 10), it is understood to be on the \(0^{\mathrm{th}}\) octave. If the octave \(o\) is not in range \([0,\cdots,10]\), then it is replaced with \(o~(\mathrm{mod}~10)\).

[7]:

if omusic.NOTES == omusic.NOTES_MIDI:

assert note_s2i("C") == note_s2i("C0")

[8]:

from omusic import Pitch, Interval

Intervals

An interval is the musical distance between two notes. An interval between two notes is harmonic if these notes are played at the same time; otherwise, the interval is melodic. The half-step is the smallest apartness commonly used in Western omusic. A whole-step equals two half-steps.

In integer notation, an interval be denoted by a simple integer. In text however, intervals are often communicated by name. The following sections explain how these names are formed.

Generic Intervals

Generic intervals measure the difference between the staff positions of two notes. In practice, this measure ignores accidentals: \(\mathrm{C}\text{--}\mathrm{D}\) are one genetic step apart, but so are \(\mathrm{C}\text{--}\mathrm{D}\#\). This is because \(\mathrm{D}\) and \(\mathrm{D}\#\) are on the same staff.

Generic intervals, like people, have names. For example, \(\mathrm{C}\text{--}\mathrm{D}\) are a second apart. The following table lists these names.

Step difference |

Name of Interval |

|---|---|

0 |

First / Prime |

1 |

Seconds |

2 |

Thrids |

3 |

Fourths |

4 |

Fifths |

5 |

Sixths |

6 |

Sevens |

7 |

Eights |

Specific Intervals

Specific intervals are measured on both staff and half steps. For example, recall that \(\mathrm{C}\text{--}\mathrm{D}\) are a generic second apart. Because they are also 2 half steps apart, they are a major second apart. \(\mathrm{B}\text{--}\mathrm{C}\) on the other hand are a minor second apart because they are a genetic second apart while being just one half step apart. Some examples follow:

Apartness |

Name |

|---|---|

2 |

Major Second |

4 |

Major Third |

5 |

Perfect Fourth |

7 |

Perfect Fifth |

9 |

Major Sixth |

11 |

Major Seventh |

12 |

Perfect Eighth (Perfect octave) |

The terms “major” and “perfect” refer to the interval’s quality. Only the 2nds, 3rds, 4ths, 6ths, and 7ths are major intervals. The rest (1sts, 4ths, 5ths, and 8ths) are perfect intervals instead.

A minor interval has 1 fewer half step than a major interval. An augmented interval has one more than a major interval. An augmented interval has one more half step than a perfect interval. A diminished interval has one less half step. Minor intervals can be diminished by subtracting yet another half-step. The following figure illustrates these relations:

The following cell seeks to capture this behaviour. In particular:

INTERVALSmaps every name of an interval to an apartness (by half steps).apartness_to_namemaps every apartness to a set of names.name_apartness, when given two notes, returns a probable name for hte interval between them.

Check if the aforementioned intervals are correctly named:

[9]:

_pairs: list[tuple[str, str]] = [

('C#', 'D'),

('C', 'D'),

('C', 'D#'),

('B', 'C'),

]

for __from, to in _pairs:

print(f"The interval from {__from}"

f" to {to} is"

f" {name_interval(__from, to)}")

The interval from C# to D is minor 2

The interval from C to D is major 2

The interval from C to D# is augmented 2

The interval from B to C is minor 2

Cheat Sheet

Having suffered through the Library of Alexandria, you have earned yourself access to a cheat sheet. Enjoy :D

[10]:

persephone: list[tuple[int, str]]\

= sorted([(b, a) for a, b

in omusic.INTERVALS.items()])

import tabulate

tabulate.tabulate((p := persephone,

[(*x, *y) for (x, y)

in zip(p[:int(len(p)/2)],

p[int(len(p)/2):])])[1],

headers=["Half-Step Difference",

"Name"]*2,

tablefmt="html")

[10]:

| Half-Step Difference | Name | Half-Step Difference | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | augmented 7 | 5 | perfect 4 |

| 0 | diminished 2 | 6 | augmented 4 |

| 0 | perfect 8 | 6 | diminished 5 |

| 0 | prime 1 | 7 | diminished 6 |

| 1 | augmented 1 | 7 | perfect 5 |

| 1 | augmented 8 | 8 | augmented 5 |

| 1 | minor 2 | 8 | minor 6 |

| 2 | diminished 3 | 9 | diminished 7 |

| 2 | major 2 | 9 | major 6 |

| 3 | augmented 2 | 10 | augmented 6 |

| 3 | minor 3 | 10 | minor 7 |

| 4 | diminished 4 | 11 | diminished 1 |

| 4 | major 3 | 11 | diminished 8 |

| 5 | augmented 3 | 11 | major 7 |

The reach function “reaches up” from a given note by either the given apartness (in half steps) of an interval specified by name.

To show the correctness of reach, assuming that name_interval is correct, try to “reach” from every note to every other note by the name of the interval between them.

[11]:

for name_x in omusic.NOTE_NAMES:

for name_y in omusic.NOTE_NAMES:

same_class(reach(name_x, name_interval(name_x, name_y)), name_y)

Inverting Intervals

To invert a group of notes is to move the lowest note an octave higher. This is easy to implement.

Inverting an interval carries a related meaning. Suppose that inverting C-G gives G-C: inverting the interval between C-G should yield the interval between G-C. The invert_interval function captures this behaviour.

Perfect intervals always invert to perfect intervals. A factoid: inverting the perfect 4th and the perfect 5th give each other.

[12]:

assert invert(omusic.INTERVALS["perfect 5"])\

== omusic.INTERVALS["perfect 4"]\

and invert(omusic.INTERVALS["perfect 4"])\

== omusic.INTERVALS["perfect 5"]

Reaching “up” from a note by a given interval, then again by the invert of that interval, should produce that note (albeit an octave higher). Together, reach and invert_interval allows us to test this:

[13]:

for note, interval in zip(omusic.NOTES,

omusic.INTERVALS.values()):

assert same_class(note,

reach(reach(note, interval),

invert(interval)))

Scales

This section is developed with help from Play Guitar in 14 Days by Troy Nelson.

A scale is an ordered sequence of notes. In western music, a scale (particularly a diatonic scale) is constructed by counting notes from a starting note. This starting note is its home note (or tonic); the pattern of counting is either its key (if the pattern is major or minor) or its mood (if the pattern is, for example, ionian). These inconsistencies are due to historical reasons.

Scale Degrees 音级

The scale degree is the position of a particular note on a scale, up from the tonic. The \(i^\mathrm{th}\) degree can be denoted as \(\hat{i}\).

For a heptatonic scale, these degrees have the following names:

Position |

Name |

|---|---|

8 |

Tonic (again) |

7 |

Leading Tone / Subtonic |

6 |

Submediant |

5 |

Dominant |

4 |

Subdominant |

3 |

Mediant |

2 |

Supertonic |

1 |

Tonic |

Note some peculiarities: the submediant (6th) does not lead into the mediant (3rd); rather, it is the “mediant” of the dominant (5th) and the subtonic (7th).

Also, the 7th node can have two names (“may”, since some tutorials just call it the supertonic): If it is one half step below the tonic, then it is the leading tone; if it is one whole step below the tonic, then it is the subtonic.

Major and Minor Scales

The major scale is a seven-note scale constructed form a specific pattern of half steps and full steps. Here, such patters are represented as a sequence of 2s and 1s. The minor scale uses a similar pattern.

{TODO}

For scales, the word key can communicate two things: (a) if a scale is major or minor (“the scale is in major key”), or (b) which note is the tonic of the scale (“the scale is in the key of A”). In the latter case, the scale itself is the key. Better not think too hard about it.

Modes

The adjectives “major” and “minor” can apply to many things, from intervals to keys (modes) to scales. For convenience, this library describes all sequences of intervals as modes. See omusic.modes for pre-defined modes.

[14]:

import omusic.modes as modes

Constructing Scales

To construct a scale from a tonic and a mode, start counting from the tonic according to the mode. The construct_scale function captures this behaviour.

[15]:

scale("C", modes.MINOR_MELODIC)

[15]:

['C0', 'D0', 'D#0', 'F0', 'G0', 'A0', 'B0']

Relative Scales

Relative scales contain the same notes, though not arranged in the same order. To build evidence that construct_scale is correct, see if it correctly constructs relatives.

Here’s every pair of relatives from the circle of fifthssss. Ssss. Hisssss.

[16]:

from omusic import same_class, name_interval

CIRCLE_OF_LIFE: list[tuple[str, str]]\

= [("C", "A"),

("G", "E"),

("D", "B"),

("A", "F#"),

("E", "C#"),

("B", "G#"),

("F#", "D#"),

("C#", "A#"),

("G#", "F"),

("D#", "C"),

("A#", "G")]

for major_key, minor_key in CIRCLE_OF_LIFE:

assert same_class(

scale(major_key, modes.MAJOR),

scale(minor_key, modes.MINOR),)

interval_name: str = name_interval(major_key, minor_key)

print(f"Interval from {major_key} to {minor_key}"

f" is {name_interval(major_key, minor_key)},"

f" or {omusic.INTERVALS[interval_name]} half steps.")

Interval from C to A is major 6, or 9 half steps.

Interval from G to E is major 6, or 9 half steps.

Interval from D to B is major 6, or 9 half steps.

Interval from A to F# is major 6, or 9 half steps.

Interval from E to C# is major 6, or 9 half steps.

Interval from B to G# is major 6, or 9 half steps.

Interval from F# to D# is major 6, or 9 half steps.

Interval from C# to A# is major 6, or 9 half steps.

Interval from G# to F is diminished 7, or 9 half steps.

Interval from D# to C is diminished 7, or 9 half steps.

Interval from A# to G is diminished 7, or 9 half steps.

[17]:

interval_i2s(9)

[17]:

['major 6', 'diminished 7']

[18]:

name_interval("A", "G")

[18]:

'minor 7'

Pentatonic Scales

A pentatonic scale is a scale with five tones instead of seven. To construct a pentatonic scale from a major heptatonic scale, take items at indices \([1, 2, 3, 5, 6]\) (assuming 1-based indexing). Constructing pentatonic minor scales is similar, but uses indices \([1, 3, 4, 5, 7]\).

The function pentatonic_major and pentatonic_minor capture these behaviours. These functions can also construct pentatonic scales from other modes.

For convenience, be free to use MAJOR_PENTATONIC and MINOR_PENTATONIC.

[19]:

from omusic.modes import _pentatonic_major

from omusic.modes import _pentatonic_minor

assert modes.MAJOR_PENTATONIC \

== _pentatonic_major(modes.MAJOR)

assert modes.MINOR_PENTATONIC \

== _pentatonic_minor(modes.MINOR)

[20]:

assert same_class(

scale("C",

_pentatonic_major(modes.MAJOR)),

['C', 'D', 'E', 'G', 'A'])

assert same_class(scale("A",

_pentatonic_minor(modes.MINOR)),

['A', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'G'])

Blues Scales

Blues scales are 6-notes long. A blues minor scale is the pentatonic scale with an extra flat 5th. For example, whereas the A pentatonic scale is [‘A’, ‘C’, ‘D’, ‘E’, ‘G’], the A blues scale is [‘A’, ‘C’, ‘D’, ‘D#’, ‘E’, ‘G’] A blues major scale gets a flat third instead.

[21]:

from omusic.modes import _blues_major

from omusic.modes import _blues_minor

[22]:

assert same_class(

scale('C',

_blues_major(modes.MAJOR)),

['C', 'D', 'D#', 'E', 'G', 'A'])

assert same_class(

scale('A',

_blues_minor(modes.MINOR)),

['A', 'C', 'D', 'D#', 'E', 'G'])

[23]:

scale("A", modes.MINOR)

[23]:

['A0', 'B0', 'C1', 'D1', 'E1', 'F1', 'G1']

Harmonic and Melodic Minors

I see your harmonic minor and raise you a melodic minor.

The harmonic minor has a

Recall that the A minor is [‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, ‘D’, ‘E’, ‘F’, ‘G’]. Its harmonic minor is […, ‘E’, ‘F’, ‘G#’]; its melodic minor is [… ‘E’, ‘F#’, ‘G#’]

[24]:

from omusic.modes import _harmonic_minor

from omusic.modes import _melodic_minor

[25]:

assert same_class(

scale("A", _melodic_minor(modes.MINOR)),

['A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F#', 'G#'])

assert same_class(

scale("A", _harmonic_minor(modes.MINOR)),

['A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F', 'G#'])

Augmented and Diminished Scales

There are two kinds of diminished scales: the typical whole-half diminished scale (of intervals [2, 1, 2, 1, …]) and the half-whole diminished scale (of intervals [1, 2, 1, 2,…]).

[26]:

from omusic.modes import DIMINISHED_WHOLE_HALF

from omusic.modes import DIMINISHED_HALF_WHOLE

from omusic.modes import AUGMENTED

[27]:

assert same_class(

scale("A", modes.DIMINISHED_HALF_WHOLE),

['A', 'A#', 'C', 'C#', 'D#', 'E', 'F#', 'G'])

Chords

A chord is a combination of three or more notes. There are many ways to construct chords, such as constructing triads on a scale.

As you know, a triad is a triple of topological spaces \(\{P, A, B\};~A,B\prec P\) where \(P=\mathrm{int}(A)\cup\mathrm{int}(B)\).

What you might not know is the fact that the triad of a scale is a subset of notes in that scale at the prime, a third, and a fifth. This “prime” is the root of the triad.

[28]:

from omusic.chord import count_triad

A major triad takes a major third and a perfect fifth. Other triads are constructed with different choices of thirds and fifths’.

[29]:

from omusic.chord import count_triad_major

[30]:

assert same_class(

count_triad_major("C"),

['C', 'E', 'G'])

Inverting Triads

Like inverting intervals, inverting a triad moves the lowest note up an octave.

When the bass note, the lowest note in the triad, is its root, the triad is in root position. Inverting the triad once moves it into first inversion; inverting again moves it to the second inversion.

Alternatively, the degree of inversion can be denoted by its bass note. For example, the F major triad is ['F', 'A', 'C']; its first inversion ['A', 'C', 'F'] can be denoted by F/A.

[31]:

# invert_triad

# invert_triad_to

Seventh Chords

A seventh chord combines a triad with an interval of a seventh. There are five types of common seventh chords:

The dominant seventh uses a major triad and a minor seventh …

… and so on.

[ ]:

[32]:

assert omusic.same_class(

chord.count_seventh_dominant("C"),

['C', 'E', 'G', 'A#'])

Diatonic Triads

Every major and minor scale have seven diatonic triads, which are formed from notes on that scale.

The first triad uses the 1st, 3rd, and 5th notes counting up from the root (the root itself being the 1st). The nth triad instead counts from the nth note instead.

[33]:

from omusic.chord import triad

from omusic.chord import seventh

[34]:

seventh("C", modes.MAJOR, order=8)

[34]:

['D1', 'F1', 'A1', 'C2']

Note that this method is identical to the aforementioned approach of counting intervals.

[35]:

assert chord.count_triad_major("C")\

== triad("C", modes.MAJOR)

assert chord.count_seventh_augmented_major("C")\

== seventh("C", modes.AUGMENTED, "major")

Roman Numeral Analysis: Seventh Chords

I honestly don’t know what this means.

Neapolitan Chords

To construct a Neapolitan chord, construct a major triad (1, 3, 5) starting with the second scale degree of another scale.

[36]:

from omusic.chord import neapolitan_chord

[37]:

neapolitan_chord("A", modes.MAJOR)

[37]:

['A#0', 'D1', 'F1']

Nonharmonic Tones

[ ]:

[38]:

# for winner in list_of_scales[5:]:

# print(f"{winner[0]} {winner[1]} has matches {note_i2s(list(winner[2]))}, but not {note_i2s(list(winner[3]))}")

# # Prog rock -- scales

# # Two finger picking

# # Just go faster

# # Chord transition

# # > Major scale harmony

# # > Minor scale harmony

# # Pentatonic scale - make it easier to

# # Figure out songs

Visualisation

To visualise the fretboard, first find out which notes are on it.

[39]:

%matplotlib inline

%config InlineBackend.figure_format='retina'

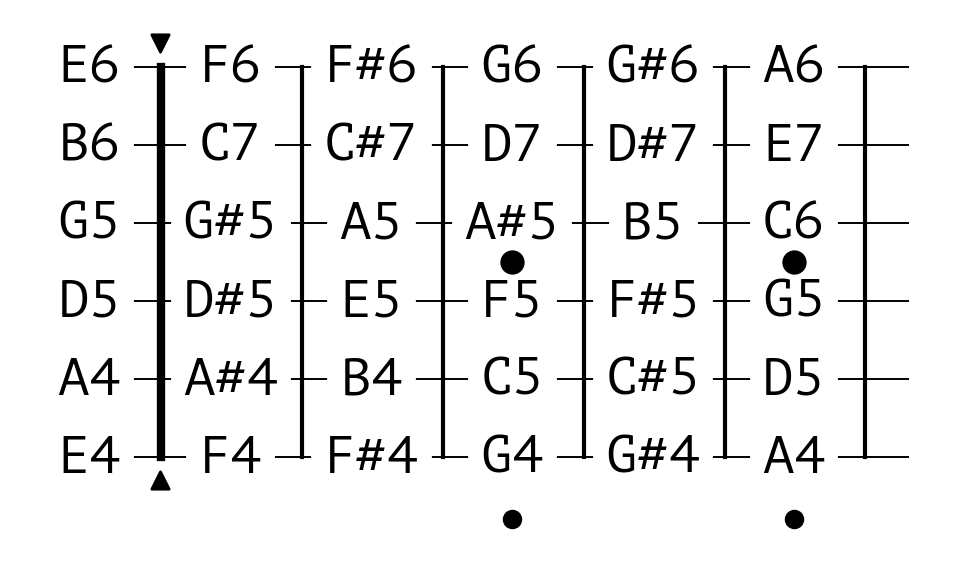

Drawing the Fretboard

Begin with drawing an empty fretboard.

[40]:

import omusic.guitar as guitar

from omusic.guitar import draw_scale

draw_scale(omusic.NOTES, 0, 6)

[41]:

triad("C5", modes.MAJOR)

[41]:

['C5', 'E5', 'G5']

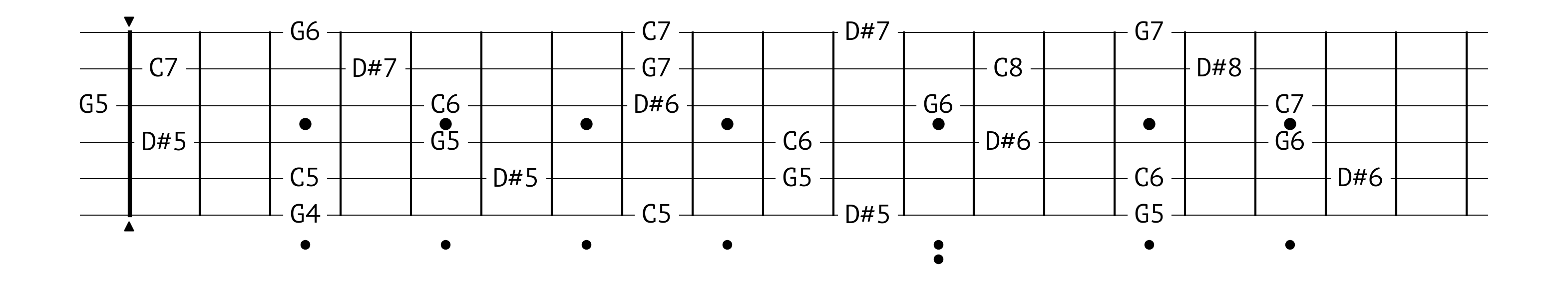

[42]:

draw_scale(triad("C5", modes.MAJOR_BLUES), 0, 20)

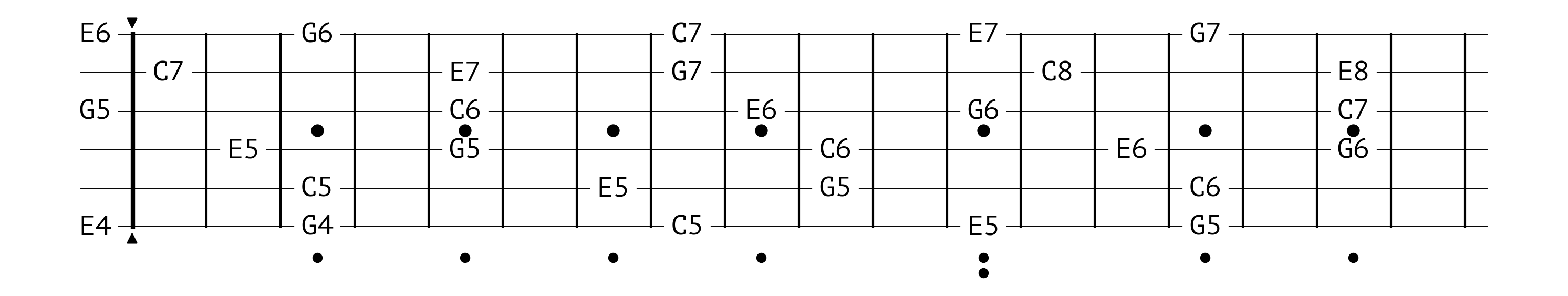

[43]:

draw_scale(triad("C", modes.MAJOR), 0, 19)

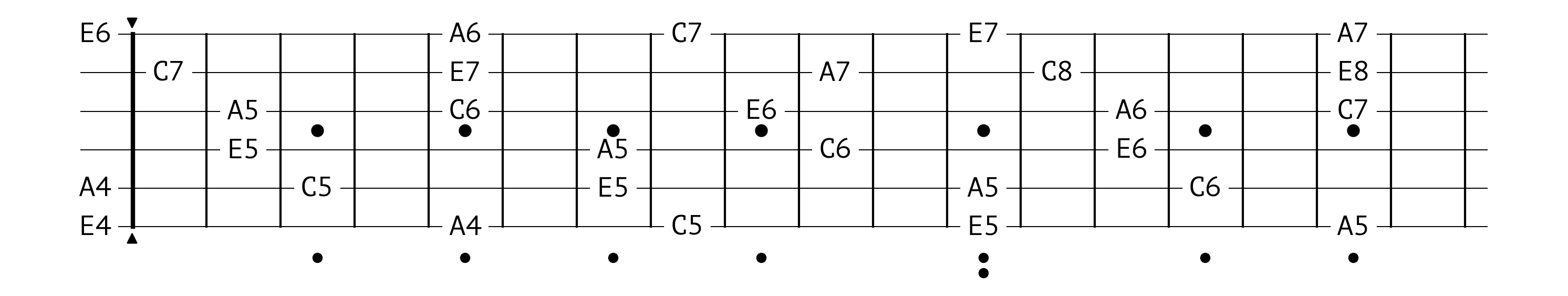

[44]:

draw_scale(triad("A5", modes.MINOR), 0, 19)

# draw_scale(construct_scale("C7", MAJOR), 0, 19)

[45]:

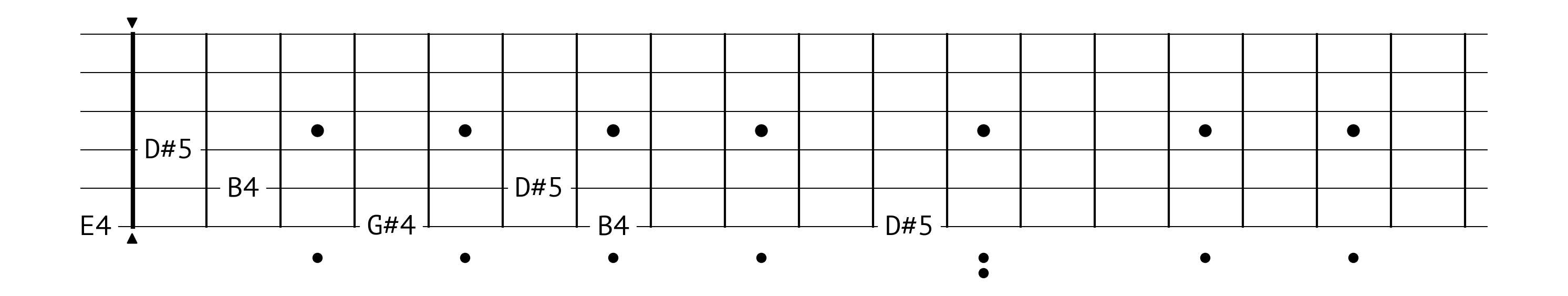

draw_scale(seventh("E4", modes.MAJOR), 0, 19, strict=True)

[46]:

from omusic.modes import *

from omusic import NOTE_NAMES

TEST_SCALES = [

[MAJOR, "major"],

[MINOR, "minor"],

[MINOR_NATURAL, "minor_natural"],

[MINOR_HARMONIC, "minor_harmonic"],

[MINOR_MELODIC, "minor_melodic"],

[IONIAN, "ionian"],

[DORIAN, "dorian"],

[PHRYGIAN, "phrygian"],

[LYDIAN, "lydian"],

[MIXOLYDIAN, "mixolydian"],

[AEOLIAN, "aeolian"],

[LOCRIAN, "locrian"],]

list_of_scales = []

for key in NOTE_NAMES:

for _scale in TEST_SCALES:

this_scale_set = set([x[:-1] for x in scale(key, _scale[0])])

that_scale_set = set(["C", "F", "G"])

list_of_scales.append([

key,

_scale[1],

this_scale_set.intersection(that_scale_set),

this_scale_set.difference(that_scale_set),

that_scale_set.difference(this_scale_set)

])

list_of_scales.sort(key=lambda x: len(x[2]),

reverse=True)