Collect and Plotting Statistics

This tutorial explains how to collect and plot runtime statistics in two ways:

The Manual Approach: Collecting fitness values directly from individuals.

Automating with Watcher: Collecting and reporting fitness values using the

evokit.watchmodule.

[1]:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import random

random.seed(1)

Construct an Algorithm

For convenience, this tutorial uses a pre-built algorithm that uses the following components.

Component |

Choice |

|---|---|

Individual |

Binary string |

Evaluator |

OneMax |

Selector |

Elitist truncation |

Variator |

Mutation ( |

To mimic the size of a practical problem, let’s use the following hyperparameters. All choices are defined as constants in the following cell; please adjust them as you see fit.

Parameter |

Choice |

|---|---|

Population size |

1000 |

Individual size |

10000 |

Epochs |

30 |

[2]:

MUTATION_P: float = 0.2

STEP_COUNT: int = 30

POP_SIZE: int = 1000

IND_SIZE: int = 10000

from evokit.evolvables.prefabs import make_onemax

The Manual Approach

Let’s begin with collecting and plotting fitness values by hand. Recall (from the Algorithm tutorial) how everything falls into place:

The algorithm returned by

make_onemaxis an instance ofHomogenousAlgorithm, which means it has one.population.The

.populationis an instance ofPopulation, which means it is a collection of individuals.Each individual is an instance of

BitString, a subclass ofIndividual. All subclasses ofIndividualinherits the.fitnessattribute.

We want to plot the fitness value of the individual with the highest .population. Population.best(...) conveniently returns one such individual; we need only collect and plot its .fitness.

[3]:

best_fitnesses: list[float] = []

algo = make_onemax(POP_SIZE,

IND_SIZE,

MUTATION_P,

max_parents=0)

for _ in range(STEP_COUNT):

algo.step()

best_fitnesses.append(algo.population.best().fitness[0])

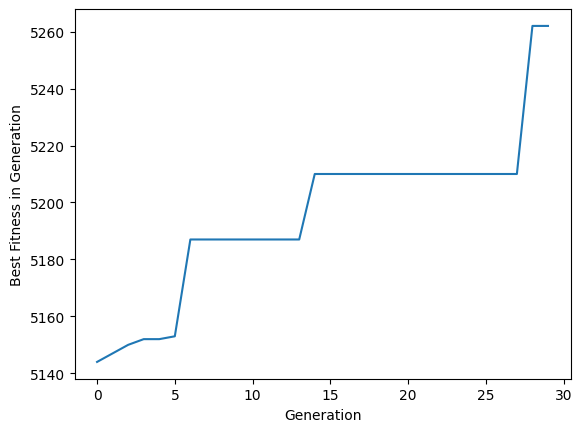

[4]:

plt.plot(range(STEP_COUNT), best_fitnesses)

plt.xlabel("Generation")

plt.ylabel("Best Fitness in Generation")

plt.show()

Automating with Watcher

The evokit.watch module can help collect and report runtime statistics. Compared to the manual, a watch.Watcher can run as soon as events happen, work with a wide range of algorithms, and report data in a easily comparable format.

Components of the module fall into into three categories:

The

Watcherclass, which can bothbe called to create simple watchers with custom handlers and

serve as a base class for more complex watchers.

The

.visualiersubmodule, which contains tools for plotting collected records.Stock watchers that collect, for example, cpu and memory usage.

This tutorial mainly discusses #1.a and #2.

Inspecting Available Events

The watch module performs its function with the Watcher class. A Watcher can be attached to an Algorithm and respond to certain events fired by the algorithm. Please see the Algorithm tutorial for how an algorithm fires events.

From the user’s perspective, an algorithm can only fire events it declares in .events and .automatic_events. Let’s check these!

[5]:

algo_2 = make_onemax(POP_SIZE,

IND_SIZE,

MUTATION_P,

max_parents=0)

print(f"events: {algo_2.events};"

f" automatic events: {algo_2.automatic_events}")

events: ['POST_VARIATION', 'POST_EVALUATION', 'POST_SELECTION']; automatic events: ('POST_STEP',)

These attributes correspond to two sorts of events:

.eventscontain manual events. These events can be fired by calling.update(typically from inside.step(...))..automatic_eventsare fired regardless of how the algorithm is coded. For example,POST_STEPfires after.step(...)is called but before control returns to the caller.

Crafting an Watcher

An watcher must be created with accounting.Watcher. The constructor can take five parameters:

A list of

eventsthat can trigger collection.A callable

handlerthat collects data from the associated algorithmAn optional

stridethat can space out collectionsAn optional, position-only

watch_post_stepthat decides if the watcher triggers onSTEP_END. The last parameter is there for convenience: settingwatch_post_steptoTruehas the same effect as addingSTEP_ENDtoevents.An optional, keyword-only

timer. The defaulttime.process_time, while useful for HPC tasks, records the CPU time, which can be much shorter than the actual run time. Let’s usetime.perf_counterto drag things out a little.

Let’s declare an Watcher that collects the best fitness from a population only after a step ends. As the type hint shows, the watcher collects…

… from a

SimpleLinearAlgorithmofBitStrings,a fitness value of type

float.

[6]:

from evokit.watch import Watcher

from evokit.evolvables.algorithms import SimpleLinearAlgorithm

from evokit.evolvables.bitstring import BitString

import time

fit_acc = Watcher[SimpleLinearAlgorithm[BitString], float](

events=SimpleLinearAlgorithm.events,

handler=lambda algo: algo.population.best().fitness[0],

watch_post_step=True,

timer=time.process_time)

Registering a Watcher

Once constructed, the watcher can be registered with an algorithm by calling Algorithm.register(...).

Internally, Algorithm.register(...) calls Watcher.subscribe(...) so that the algorithm and the watcher reference each other [^1]. The following figure illustrates this:

[7]:

algo_2.register(fit_acc)

assert fit_acc in algo_2.watchers

assert algo_2 is fit_acc.subject

Collecting Statistics

Now that everything is in place, let’s run the algorithm and see what happens!

When an event fires in the Algorithm, it calls Algorithm.update which calls Watcher.update for each watcher in the algorithm’s .watchers. Then, the watcher collects statistics from its .subject only if either (a) the event is in its .events or (b) the watcher’s .watch_post_step is True and the event is POST_STEP.

Because POST_STEP triggers only at the end of each .step(...), it’s good practice to fire it at the beginning so that we know how things started. Here goes:

[8]:

algo_2.update("POST_STEP")

for _ in range(STEP_COUNT):

algo_2.step()

To inspect what data the watcher has collected, call Watcher.report(...). Note that records collected immediately after POST_VARIATION have value=nan. This is because the variator resets the fitness values of all.

[9]:

fit_acc.report()[:4]

[9]:

[WatcherRecord(event='POST_STEP', generation=0, value=nan, time=0.6875),

WatcherRecord(event='POST_VARIATION', generation=0, value=nan, time=0.6875),

WatcherRecord(event='POST_EVALUATION', generation=0, value=5180, time=0.6875),

WatcherRecord(event='POST_SELECTION', generation=0, value=5180, time=0.703125)]

Plotting

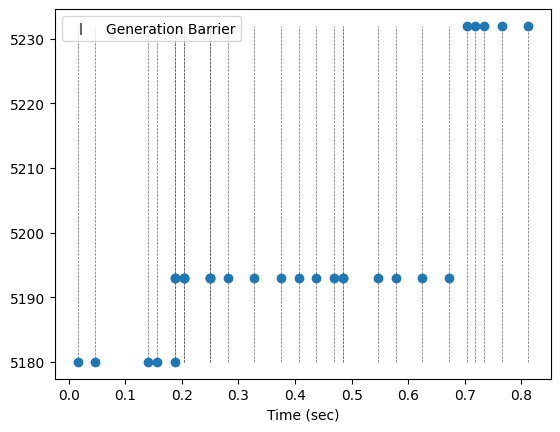

The watch.visual module has tools to plot data from a Watcher. Give it a try! Note that data points are plotted against time. This should make it easier to compare performance.

For simplicity, only end-of-generation fitness values are plotted here. The next section will be much more interesting.

[ ]:

from evokit.watch.visual import plot

plot([x for x in fit_acc.report() if x.event == "POST_STEP"],

show_generation=True,)

Now the fun begins. Recall that this experiment uses a rather ambitious mutation rate and an elitist selector. The high mutation rate increases the possibility that offspring have a lower best fitness than the parents, but the elitist selector ensures that the best parent is always retained, preventing a generational decline in fitness.

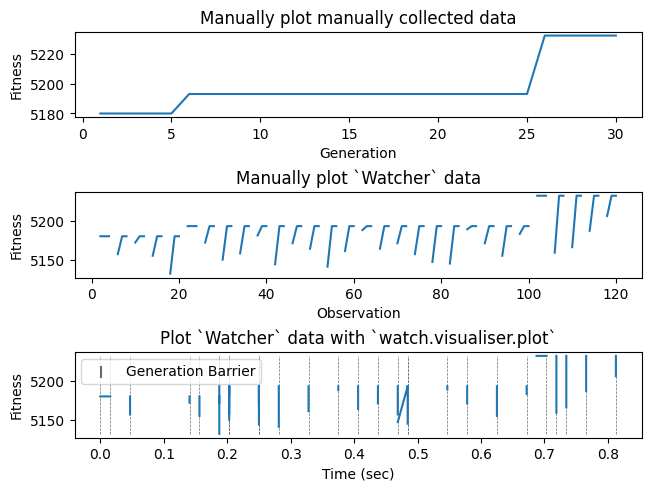

The following cell plots three figures to reflect this:

The first figure shows what could be collected with the manual approach. As we only have access to the population outside of

.step(...), there is not much chance to observe how an elitist selector operates.The second figure plots all observed fitnesses. Here, each “hockey stick” shows where the elitist selector updates the population with the best parent.

The third figure, using

watch.visual.plot, plots all data points against time. We see that generations often take different amounts of time, and that the elitist mechanism takes less time to run than what plot 2 suggests,

[ ]:

_, (ax1, ax2, ax3) = plt.subplots(nrows=3,

ncols=1,

layout='constrained')

ax3.set_title("Plot `Watcher` data with `watch.visualiser.plot`")

plot(fit_acc.report(),

show_generation=True,

axes=ax3,

use_line=True)

ax3.set_ylabel("Fitness")

ax2.set_title("Manually plot `Watcher` data")

_data = [x.value for x in fit_acc.report()]

ax2.plot(range(len(_data)), _data)

ax2.set_xlabel("Observation")

ax2.set_ylabel("Fitness")

ax1.set_title("Manually plot manually collected data")

_data = [x.value for x in fit_acc.report() if x.event == "POST_STEP"]

ax1.plot(range(len(_data)), _data)

ax1.set_xlabel("Generation")

ax1.set_ylabel("Fitness")

plt.show()